Caribbean disturbance likely to become hurricane before it moves into Gulf

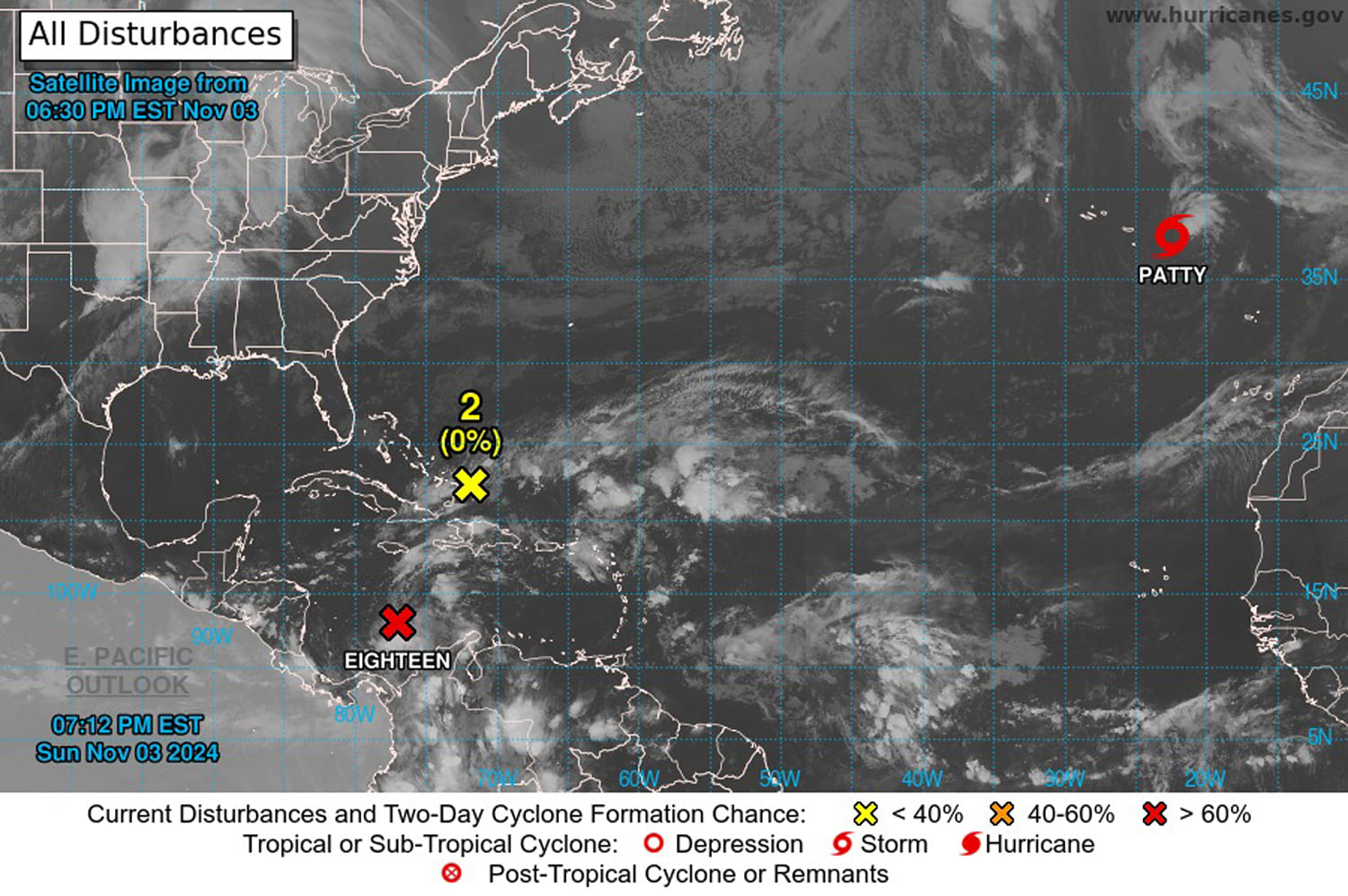

A tropical disturbance in the Caribbean is likely to become a hurricane as it passes over Cuba and into the Gulf of Mexico by midweek, federal forecasters said Sunday.

Residents of the west coast of Florida and other Gulf Coast states should monitor developments and expect at least heavy rain later in the week, the National Hurricane Center said in a series of updates and forecast discussions.

Potential Tropical Cyclone 18 is about 345 miles south of Kingston, Jamaica, the hurricane center said in a 7 p.m. update, and moving northeast at 7 mph. Sustained winds of 35 mph have been recorded, it said.

The Air’s Force 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, using Super Hercules fixed-wing aircraft, got a close look Sunday, the hurricane center said in an afternoon forecast discussion.

“Their data indicates that the system has developed a closed center,” it said, indicating the storm is organizing.

Still, the upward movement of warm air and precipitation wasn’t intense enough to call the disturbance a tropical depression, the hurricane center said. That would most likely come overnight, it said.

Hurricane formation likely

Hurricane center forecasters said there was a 100% chance the disturbance would become at least a tropical depression and a 100% chance it would strengthen after that during the week.

Wind speeds for a tropical depression max out at 38 mph. At 39 mph it becomes a tropical storm, which could happen early Tuesday, according to hurricane center forecasts.

The system is likely to organize into a hurricane, which would require sustained winds of at least 74 mph, by early Tuesday afternoon and remain one when it reaches Cuba on Tuesday or Wednesday, the center said.

But its strengthening could pause as it reaches the Gulf of Mexico, where drier air would work against it, the center said.

“Intrusions of dry air should end the strengthening process and likely induce some weakening,” it said in an afternoon forecast discussion.

By the time it reaches the northern Gulf Coast, it could have weakened to a tropical storm, the center said, noting that there are uncertainties in the long-range forecast.

If the system forms into a hurricane, it will be the 11th of the 2024 season in the Atlantic, Colorado State University meteorologist Philip Klotzbach said on X. Names available for the system include Rafael and Sara, according to the hurricane center.

Storm threats

In the meantime, the hurricane center said, hurricane conditions are possible within 48 hours on the Cayman Islands. Jamaica was under a tropical storm warning, which means winds of 39 to 73 mph should be expected in 24 to 36 hours.

The northward storm was expected to move near Jamaica on Monday and the Cayman Islands on Tuesday, federal forecasters said. It could bring coastal flooding from a storm surge and heavy rainfall of up to 9 inches, they said.

High surf will also be possible in the western Caribbean through at least midweek, the forecasters said.

Warm water as fuel

U.S. forecasters expect it to shift its north-northeast movement to the north-northwest and enter the Gulf of Mexico through the Yucatán Channel before it heads toward the Gulf Coast later in the week.

It’s still uncertain where Potential Tropical Cyclone 18 would aim once it is inside the Gulf, which has experienced extreme average sea surface temperatures that peaked at roughly 88 degrees in August and remain warm at around 75 degrees this month.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration experts say storms prefer sea surface temperatures of at least 80 degrees to form into hurricanes.

Tropical cyclones are fueled by warm sea water, which encourages vertical movement of warm air that helps the storms spin counterclockwise as they spit out rain and wind.

“When the surface water is warm, the storm sucks up heat energy from the water, just like a straw sucks up a liquid,” according to a NOAA video about how tropical storms form.

Gulf water temperatures have consistently tracked a few degrees higher than average since summer, according to data posted to X by Kim Wood, an atmospheric sciences professor at the University of Arizona.

That might help explain the rapid development and intensity of some of the season’s storms, including October’s Hurricane Milton, which went from named storm to hurricane in 24 hours, according to NOAA.

“This explosive strengthening was fueled in part by record to near-record warmth across the Gulf of Mexico,” it said.

The warmer-than-normal water is an indication of climate change, and it could be helping to fuel more intense and rapidly developing storms, experts at NOAA and the Environmental Protection Agency said.