Fungal infections are getting harder to treat

Fungal infections are getting harder to treat as they grow more resistant to available drugs, according to research published Wednesday in The Lancet Microbe.

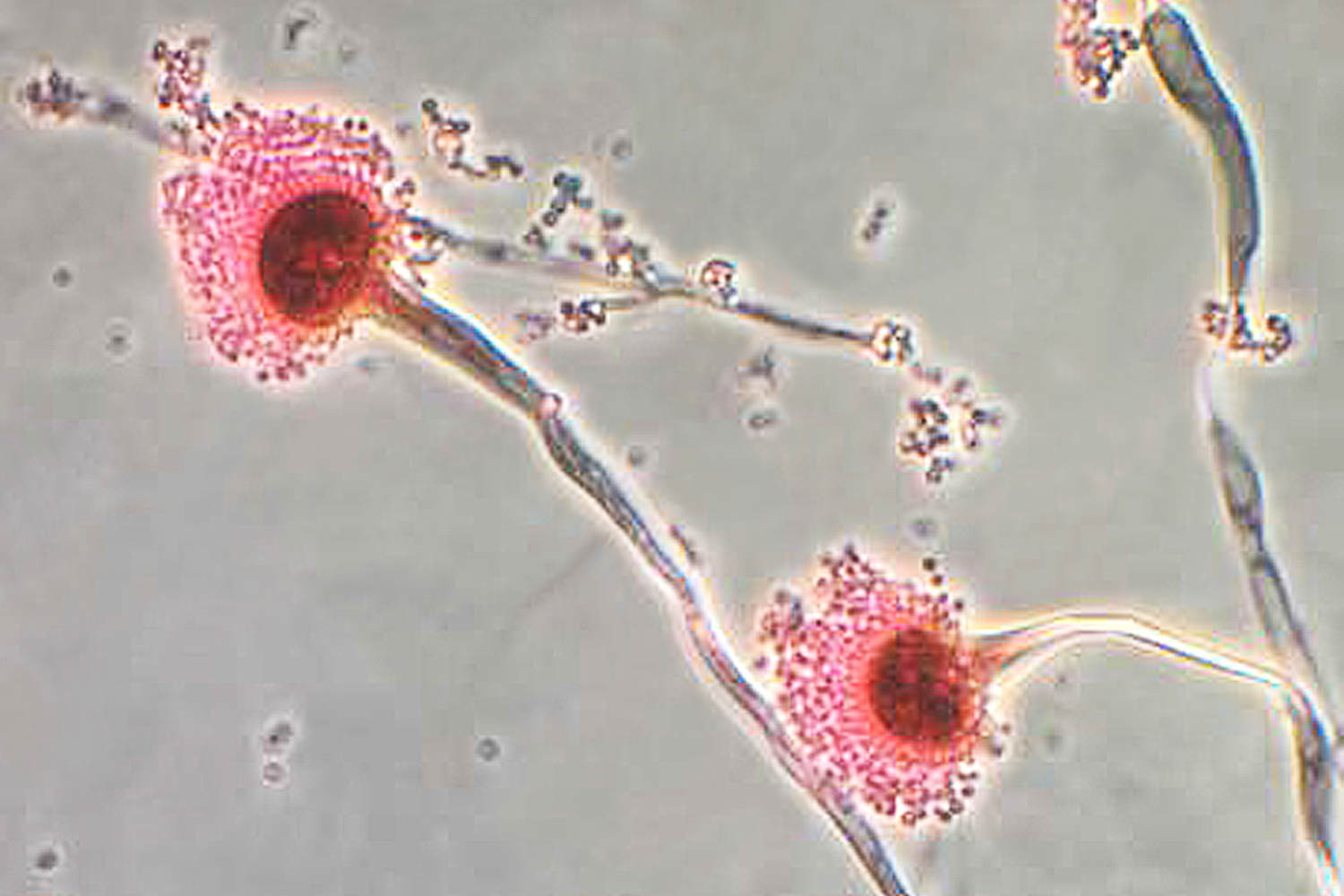

The study focused on infections caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungus that is ubiquitous in soil and decaying matter around the world. Aspergillus spores are inhaled all the time, usually without causing any problems. But in people who are immunocompromised or who have underlying lung conditions, Aspergillus can be dangerous.

The fungus is one of the World Health Organization’s top concerns on its list of priority fungi, which notes that death rates for people with drug-resistant Aspergillus infections range from 47%-88%.

The new study found that the fungus’s drug resistance is increasing. On top of that, patients are typically infected with multiple strains of the fungus, sometimes with different resistance genes.

“This presents treatment issues,” said the study’s co-author, Jochem Buil, a microbiologist at Radboud University Medical Centre in the Netherlands.

Buil and his team analyzed more than 12,600 samples of Aspergillus fumigatus taken from the lungs of patients in Dutch hospitals over the last 30 years. Of these, about 2,000 harbored mutations associated with resistance to azoles, the class of antifungals used to treat the infections. Most of them had one of two well-known mutations, but 17% had variations of these mutations.

Nearly 60 people had invasive infections — meaning the fungi spread from the lungs to other parts of the body — 13 of which were azole-resistant. In these people, nearly 86% were infected with multiple strains of the fungi, making treatment even more complicated.

“It is an increasingly complicated story and physicians may have trouble identifying whether or not they are dealing with a drug-resistant fungal infection,” said Dr. Arturo Casadevall, chair of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who wasn’t involved with the research.

Before treating an Aspergillus fungal infection, doctors look for resistance genes that can give them clues about which drugs will work best. If someone is infected with multiple strains of the same type of fungus, this becomes much less clear-cut. Oftentimes, different strains will respond to different drugs.

“Azoles are the first line of treatment for azole-susceptible strains, but they do not work when a strain is resistant. For those, we need to use different drugs that don’t work as well and have worse side effects,” Buil said, adding that some people will require treatment with multiple antifungal drugs at the same time.

The findings illustrate a larger trend of growing pressure on the few drugs available to treat fungal infections — there are only three major classes of antifungal drugs, including azoles, that treat invasive infections, compared with several dozen classes of antibiotics.

Resistance to these drugs is growing, and new ones are uniquely difficult to develop.

Humans and fungi share about half of their DNA, meaning we’re much more closely related to fungi than we are to bacteria and viruses. Many of the proteins that are essential for fungi to survive are also essential for human cells, leaving fewer safe targets for antifungal drugs to attack.

“The big problem for all of these fungal species is that we don’t have a lot of antifungals,” said Jarrod Fortwendel, a professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, who was not involved with the research. “Typically the genetic mutations that cause resistance don’t cause resistance to one of the drugs, it’s all of them, so you lose the entire class of drugs.”

Further complicating matters, the vast majority of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus stems from agriculture, where fungicides are widely used. These fungicides typically have the same molecular targets as antifungal drugs. Farmers spray them on crops, including wheat and barley in the U.S., to prevent or treat fungal disease. (The first instance of azole resistance was documented in the Netherlands, where antifungals are widely used on tulips.) Aspergillus fungi aren’t the target, but exposure to these fungicides gives them a head start developing genes that are resistant to these targets, sometimes before an antifungal drug with the same target even hits the market.

This was the source of the vast majority of the drug resistance analyzed in the study.

Fortwendel noted that fungal resistance is increasingly found around the world. “Basically everywhere we look for drug-resistant isotopes, we find them,” he said. “We are seeing this azole drug-resistance happening throughout the U.S. Those rates will likely climb.”

Any individual person’s risk of having an azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus is low, Casadevall said. Infections typically affect people who are immunocompromised and amount to around a few thousand cases per year in the U.S., Casadevall estimated. While relatively uncommon, the bigger risk is the broader trend of drug-resistant fungal infections.

“The organisms that cause disease are getting more resistant to drugs,” he said. “Even though it’s not like Covid, we don’t wake up to a fungal pandemic, this is a problem that is worse today than it was five, 10 or 20 years ago.”